Inadequate Test Tracking Process Leads to Delay in Cancer Diagnosis

Well-designed office systems are critical to the provision of safe, high-quality patient care. This case study from an OB/GYN practice in the Midwest illustrates how system failures can be detrimental to a patient’s health.

Case Details

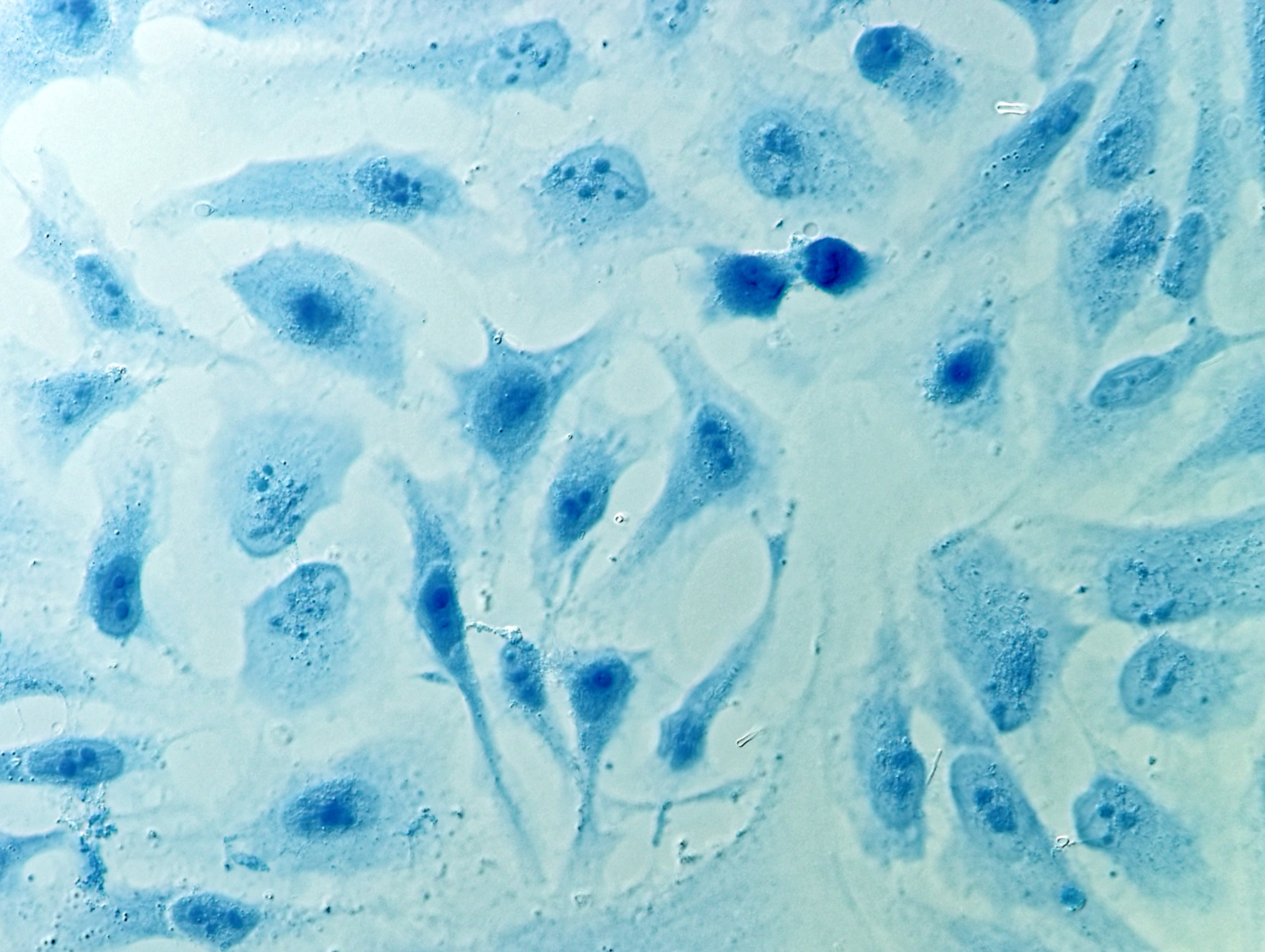

The patient was a 37-year-old female who had unwittingly contracted a sexually transmitted disease (STD). The circumstances of her situation did not lead her to suspect an infection. She presented to her gynecologist, Dr. A, in November of Year 1 for a Pap smear test. The results indicated “epithelial cell abnormality, with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance.” The report recommended a repeat Pap smear in 3–6 months if clinically indicated. However, the physician never reviewed or signed off on the report. It was included in the patient’s health record, but not flagged as a critical result.

In May of Year 2, the patient returned to the OB/GYN practice with complaints of an odorous yellow vaginal discharge. Dr. A diagnosed her with a vaginal infection (the report from November of Year 1 was not reviewed on this occasion either). The patient presented to Dr. A again in July of Year 2 with complaints of watery yellow discharge, vaginal soreness, and irritation. She also had a bladder infection. Dr. A diagnosed the vaginal symptoms as a yeast infection. Unfortunately, the report from November of Year 1 was again not reviewed.

In September of Year 2, Dr. A saw the patient again, and she reported that she had experienced abnormal vaginal bleeding since her last visit in July. She also reported that she had discharged a large piece of pink/red tissue in August. Dr. A diagnosed dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB) and prescribed a 2-month dose of drospirenone and ethinyl estradiol. It was at this visit that Dr. A first reviewed the results of the November Year 1 Pap smear. Dr. A examined the patient (the exam was normal) and did another Pap smear. The results of this Pap smear were “low-grade squamous intra-epithelial lesion.” The report recommended a colposcopy and biopsy if clinically indicated.

The patient was seen again in November of Year 2, at which time she reported a watery discharge. The patient bled when a speculum was inserted, and necrotic tissue was removed. The pathology report for the removed material indicated “cervical microinvasive squamous cell carcinoma, focal ulceration and necrosis, and severe acute and chronic inflammation.”

Because of the delay in diagnosing the cancer, the patient was no longer a surgical candidate. She received chemotherapy and radiation treatment; however, because of the intensity of the radiation, she essentially lost the lining of her vagina and can no longer engage in sexual relations. She also has a diminished life expectancy.

A medical malpractice lawsuit was filed against Dr. A. The case was settled in the high range, with defense costs also in the high range.

Discussion

In a busy healthcare practice, the number of tests and consultations that physicians and other healthcare professionals order can be staggering. From a risk management perspective, it is essential that the ordering physician review the results of any test, examination, or consultation and act on them — even if that only involves assuring the patient that his/her results came back negative.

Failure to review or act on just one critical finding can have catastrophic results. Although no one expects the practice of medicine to always be perfect, 100 percent accuracy is the standard when it comes to patient tracking. Such accuracy is generally achievable only if the tracking process is simple, but also comprehensive enough to capture all necessary information for every case. Then, the process must be consistently and completely performed on every single occasion. The policy should aim for zero tolerance in variation.

When devising or evaluating a tracking system, it often is helpful to identify the various steps in the process. Consider which steps are most prone to failures and the steps in which failures potentially could occur. What could have prevented the physician from reviewing an important report? An obvious reason is because the report was not received in the physician’s office. Why might this occur? Maybe the patient failed to have the testing done. Perhaps the specimens were lost in transit or misplaced once they arrived at the lab. It is also possible that the test was completed but the pathologist or radiologist failed to generate a report — or the report, once generated, was lost in transit.

In all of the above scenarios, the ordering physician did not receive the report. Physicians have a duty to recognize that they did not receive requested reports, and that is what patient tracking is intended to help them accomplish. No single approach is necessarily the best way to accomplish patient tracking. Some healthcare practices prefer to use electronic methods, while others still rely on paper-based methods. What is crucial is that the method is simple, capable of capturing all of the necessary data, and that providers and staff can adhere to it without exception.

A process for identifying reports not received is just one aspect of patient tracking. Healthcare practices also need to be cognizant of tracking failures that can occur after results are received at the office. In this case study, for example, the patient’s results were received, but Dr. A never reviewed or signed off on them. Practices need internal processes to ensure providers review and acknowledge all test results. Documentation should include (a) the results of the test, (b) patient notification of the results, and (c) clinical decisions based on the results — even if the decision is to take no action.

One strategy that healthcare practices can employ is assigning a staff person with the responsibility of ensuring that all reports have been reviewed (with acknowledgment by means of the healthcare provider’s initials and date). The responsible individual can monitor to make sure no reports are filed prior to review and signoff. Although this might be a labor-intensive activity, it can prove vital to the practice’s patient safety efforts.

Healthcare practices also should consider working with their reporting sources to devise a process in which critical test results are “flagged” for immediate attention. This might involve a color-coding scheme, letter classification, or other visual identifiers; the use of secure texting or email; or, preferably, picking up the phone and talking with the ordering physician. The approach that will prove both workable and reliable will depend on the needs of each healthcare practice.

Additionally, providers should encourage patients to follow up with the healthcare practice if they do not receive their results within a specified timeframe. Engaging patients in the diagnostic process can provide an additional safeguard to prevent critical results from slipping through the cracks.

A final point for discussion relates to the phrase “if clinically indicated,” which commonly appears in test reports. This language correctly acknowledges that it is the ordering provider who is responsible for assimilating all of the data and developing or making any changes to the patient’s treatment plan based on the results. The ordering clinician should document his/her rationale for ordering or not ordering further clinical steps based on the test results. This documentation establishes the provider’s efforts to provide quality patient care — and it might be essential in the defense of a malpractice claim.

Conclusion

Sadly, in this particular case, implementation of several simple steps — such as adhering to a “review before filing” process, sufficient review of the patient’s record before or after the visit in May of Year 2, or a process for reporting all test results to the patient — would likely have resulted in a more timely diagnosis.

A strict emphasis on well-defined processes might seem like bureaucratic overkill; however, if a healthcare practice has efficient and structured processes in place — and if they are closely followed — then errors and oversights, like the ones that occurred in this case, are less likely to happen, improving patient safety and reducing liability exposure.